|

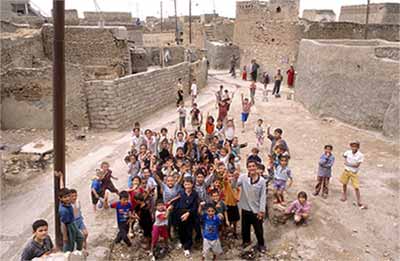

Reviews "The Last Assyrians" (Les Derniers Assyriens) is an amazing documentary about the history of the Aramaic-speaking Christians from ancient Mesopotamia until their present-day existence in the Middle East. For six years Director Robert Alaux researched and wrote this historic documentary. It is the first film that tells the complete history of the Assyrian Chaldean Syriac people. History overlooks how they suffered from massacres, hunger and starvation during the1915 genocide; and the international community has not protected these people in their homeland after decades of mass exodus. Despite their pain and suffering this indigenous Christian community, including the Diaspora, seek justice, peace, prosperity, security, and solidarity in the Middle East. Through archival footage, maps animations and interviews with religious leaders, academic scholars and famous singers, the director brings the history of this Christian population in the Middle East and in the Chaldo-Assyrian-Syriac Diaspora alive. Some of the people interviewed are: Patriarch of Babylon for the Chaldeans since 2003, Emmanuel III Delly; Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East Mar Dinkha IV; Mar Raphael I Bid Awid, Chaldean Catholic Patriarch (from 1989 until 2003); Dr. Sebastian Brock, Oxford University; Linda George, famous singer; Juliana Jendo, famous singer; and Dr. Joseph Yacoub, Lyon University. In 53 minutes the film explains how various Mesopotamian ethnic groups came together through culture, language, land, and religion only to be taken over by other ethnic groups through the centuries. More than 3,000 years ago during the time of Ur, the Sumerians had invented mathematics, writing and the wheel. The two reigning cities were Babylon on the Euphrates River and Nineveh on the Tigris River. At the time Aramaeans were like Arab Bedouins that roamed the land, but they established their kingdoms eventually and cultivated the lands. They had cultural contact with Phoenicians (present-day Lebanon). Although the Akkadian language (Assyrian cuneiform characters) was in use, more people spoke and wrote Aramaic over time because the language consisted of only 22 letters. In 612 b.c.e., the Chaldeans crushed the Assyrian Empire, seized Jerusalem and expelled the Jews to Babylon. The Aramaic language spread to Palestine. Christianity began in Palestine and spread through the oral and written traditions of the Aramaic language -- the language Jesus spoke. In Persia the official language was Aramaic. Even though the Nestorians split from the Roman Christian Church and began the Assyrian Church of the East, and the Syriac Church became independent also, all of these people spoke the Aramaic language. In 630 c.e., Muslim Arabs invaded the Middle East and the indigenous Christian community welcomed them. There were churches across Arabia so Christians and Muslims lived together in peace for decades. In Damascus, the Christians created Muslims monuments and shared their church. In 705 c.e., the church became the Umayyad Mosque. Over time the Arabic language and Islam became dominant, so when people spoke Aramaic they identified themselves as Christians. In the seventh century, Nestorian monks spread Christianity to India, Mongolia and China to approximately 60 million people after three centuries. Ancient Aramaic scripts were found in these regions by Jesuit missionaries centuries later. In 1258 c.e., the Mongols invaded Baghdad and massacred the Muslims. Initially the Mongol invaders showed obedience to the Patriarch of Baghdad. But later the Mongols chose Islam and slaughtered Christians. The descendents of the Aramaic-speaking people survived only in mountainous areas. For the most part the people were left undisturbed throughout the Ottoman Empire. They created more monasteries, safeguarded ancient Syriac scripts and lived simple, rustic lives close to nature. Eventually the pope wanted to bring these people back into Rome's fold. People who accepted his authority were called Chaldeans of the Chaldean Catholic Church. Even though Chaldeans, Nestorians and Syriacs differed on religious details they spoke Aramaic and they shared their Christianity and ethnic identity. During the 19th century ethnic groups began to identify strongly with the concept of nationalism, so Arabs, Chaldo-Assyrians, Kurds, Turks and Persians became more separated communities. During WW I, the Turks massacred over one million Armenians, and hundreds of thousands of Chaldo-Assyrians and Syriacs. This tragic moment in history is more hurtful to these communities because past and current governments dispute what happened and do not want to acknowledge that an ethnic and a religious genocide took place. This pain and suffering carries from generation to generation in the collective memory of the people. When Saddam Hussein came to power, he required submission from all Chaldo-Assyrians. He considered them Christian Arabs. In 1979, the Assyrian Democratic Movement was created. In 1991, the Assyrian Aid Society raised money for the reconstruction of Christian villages destroyed by Saddam who was fighting the Kurds, and to build Syriac-speaking schools. With the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003, Islamic extremists threatened the Christians in Iraq who have been seeking refuge in neighboring Arab countries and abroad by the thousands. With regards to the current population, estimates range from 300,000 to 1,000,000. "They threaten our women and our children in the streets," one religious clergyman said. Now they worry about the stability of the country and their future in it. "We will stay 'till the end and the Lord will help us; circumstances or war or other difficulties will not dissuade us," Emmanuel Delly said. When I asked the director why he did not explore the reality on the ground with regards to the violence and the kidnappings, he said, "Even if they suffer a lot, something very important happened in the North of Iraq: for the first time they did not say 'we are poor victims and we try to resist,' but we are proud and we want to affirm our culture (Syriac schools, big meetings and festivals . . . )." Anyone who sees this film will come away with a good understanding of the Chaldean Assyrian Syriac peoples, along with their past and present struggles from a humanistic view. The film is an excellent, educational opportunity that maintains viewer interest through scenes of their daily life, the natural landscape of Iraq, Turkey, Syria and the archaeological and religious sites of the Middle East. It shows the Diaspora in the USA and Europe also. When asked why he made a film about the Aramaean Christians, Robert Alaux said: "I respect them a lot and I admire them for their courage." Journalist Sonia Nettnin writes about social, political, economic, and cultural issues. Her focus is the Middle East.Copyright © 1998-2007 Online Journal Email Online Journal Editor |